Policy shapes the rules and systems that affect how societies function—from climate regulations to public health programs to economic reforms. Because policy decisions often impact millions or even billions of people, careers in this field can be one of the most powerful ways to create positive change in the world.

For people who are good at thinking strategically about complex problems, have strong interpersonal skills, and are willing to persist through the many hurdles in the way of successful policy change, policy careers can be among the most impactful available.

It addresses some of the most important considerations about this topic, though we might not have looked into all of its relevant aspects, and we likely have some key uncertainties. It’s the result of our internal research, and we’re grateful to Ishita Batra for advice and feedback.

Note that the experts we consult don’t necessarily endorse all the views expressed in our content, and all mistakes are our own.

What do we mean by policy?

When we talk about policy careers, we’re referring to work that shapes the decisions made primarily by important public institutions like governments and international organizations. This is intentionally broad—policy work spans everything from drafting legislation to setting technical standards, from allocating government budgets to determining how existing policies actually get implemented on the ground.

By its nature, national and international policy usually operates at a serious scale. Whether it’s a regulation affecting millions of consumers, a trade agreement between nations, or a budget decision that redirects billions in spending, policy work can comprise decisions that affect huge numbers of people. This makes it relevant to virtually every cause area you might care about, from global health to climate change to emerging technologies, though as we’ll cover later, this varies across regions and governments.

Though the exact process for developing policy varies by country and organization, it can be broadly divided into several steps:

- Research. This is the stage where policy ideas and proposals are formed, both by people within government and outside, in organizations such as think tanks, research nonprofits, and academia. Not all policy goes through a dedicated research stage, but much does.

- Advocacy. For a policy to be adopted, it needs support from the right people. At this stage, the goal is to get traction from people within the government who can take the policy forward. Gaining public support is also often desired to help convince policymakers.

- Adoption. In the adoption stage, a policy is put through the formal process that decides whether it will be approved or not. The specifics here vary quite a bit, but it involves things like parliamentary or congressional votes, executive orders, or sign-offs from other senior decision makers, like ministers.

- Implementation. Once a policy is accepted, it needs to be implemented and enforced. This is far from trivial–implementing policy is often complicated, and even a good policy can fail due to poor implementation.

- Monitoring and evaluation. The policy process often doesn’t stop there. After policies are implemented, many are monitored, evaluated, and critiqued over whether they’re working well. Over time, decisions are made on whether to maintain a policy, amend it, or terminate it.

Because of the huge variety of work that goes into policy, broadly construed, it’s hard to give one-size-fits-all advice about the field. It’s a field that accommodates a few different types of work, and can be pursued by people with various skillsets. As such, we intend this article as a starting point for someone interested in this area–but it’s far from a comprehensive guide. To help with this, we’ll link to other resources that you can use to get a fuller understanding of the wide range of options available in the policy space and help you dive deeper into more specific policy paths.

Where might you work?

Because policy is a process with many steps, there are quite a few different kinds of roles that can influence it. The types of organizations you can work in look something like this:

Governments. Perhaps the most obvious option, national governments house many people working on both the design and implementation of policy. This includes more general roles within a country’s civil service, as well as more specialist expert advising and consultation roles. Local governments–such as for specific regions or cities–may also be promising routes, though we’d expect most important policy roles to exist within national governments due to their scale.

International organizations. There are many large international organizations, like the United Nations, European Union, and the World Trade Organization, that have significant policy influence on a global scale. These institutions are major global players in the formation of crucial policy decisions. For instance, the UN plays an important role in regulating the possession and use of nuclear weapons, and formed the Sustainable Development Goals, a widely adopted set of targets for development efforts. The EU forms policy that applies to its 27 member states (and affects many other countries indirectly). And the World Bank distributes over $100 billion in development finance each year.

Political roles. Governments also host political roles–tied explicitly to political parties or candidates–that aren’t part of the civil service. Naturally, this includes politicians themselves, who play a crucial role in passing policy. It also includes those who work for politicians and political parties who help develop and advise on policy, whether they’re in government or the opposition.

Think tanks, NGOs, and advocacy groups. These are organizations external to governments and international organizations that research policies and advocate for their uptake. Many of these groups have tight relationships with governments, such as RAND in the US. Others work more to influence public opinion, driving policy change from the outside. Naturally, roles in these organizations tend to focus more on policy research, design, and advocacy, though NGOs also often have a role in implementation. Roles in think tanks also tend to be more specialist, requiring deeper subject expertise.

Academia. Academic research can also influence policy. Though some of this influence is incidental, academic research is often conducted and funded with the intention of informing policy decisions. This influence can happen both through conventional peer-reviewed research publications and government consultation.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it captures the majority of policy-relevant roles. It’s worth noting that they’re also not mutually exclusive career paths–in fact, it’s very common to hold policy roles across these organization types throughout a single career.

Resource spotlight

The blog run by Impactful Government Careers provides great tips for strategising within governmental policy careers.

How promising is policy?

Policy is an important tool, but does this translate to an impactful career? In this section, we’ll talk about the important changes policy can make, how policy priorities can vary by context, and how much good an individual could achieve in this path.

Policy can bring about significant change

Policy is a tool that often has enormous leverage–it affects how huge numbers of people behave, how important systems function, and how large sums of money are distributed. When it goes well, this can lead to positive change on a massive scale. Here are just a few examples of highly impactful policies across different cause areas:

Economic growth. Successful pro-economic growth policies have had dramatic positive effects on huge numbers of people. Through growth-oriented policies starting in the 1970s, China has transformed from a country with widespread poverty to lifting nearly 800 million people above the poverty line.

Animal welfare. Tens of billions of animals are slaughtered each year, with the vast majority of them experiencing miserable living conditions while they’re reared. Because of the scale of this suffering, policy improvements can be hugely impactful. For example, the UK’s ban on battery cages for hens improved the welfare of many tens of millions of chickens since the policy was passed in 2012.

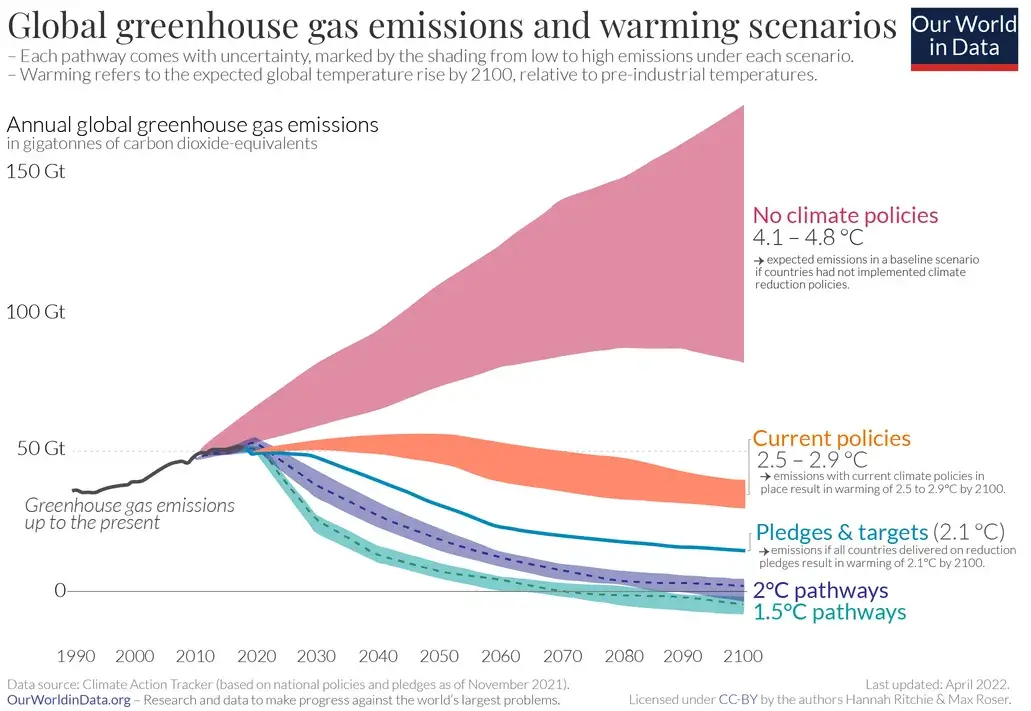

Climate change. It goes without saying that climate change is an important global problem. Thankfully, it now looks likely that we’ll avoid some of the most severe effects of climate change thanks to a host of policies adopted widely. Though there’s still a lot more to do, these policies will have positive consequences for billions of people.

International aid. Effective foreign policies have had enormous positive effects. PEPFAR, the US government’s HIV/AIDS program launched in 2003, has saved as many as 25 million lives in low-and middle-income countries. Unfortunately, however, its future looks uncertain at the time of writing.

Biosecurity. Global pandemics are an important threat to global health. Unfortunately, governments have systematically underinvested in methods to detect and protect against them. Though this is still the case, organizations like SecureBio and 1DaySooner are effectively advocating for policies that would meaningfully reduce the chance of another global pandemic.

So, there’s a great positive case for policy work–it really can be a force for enormous good. But it’s important to bear in mind that policy can go wrong. Even well-intentioned efforts to improve the world can go awry.

For example, economic policies in Zimbabwe in the 1990s led to disastrous hyperinflation. Punitive ‘three strikes’ policies in the US, intended to reduce crime, may actually have raised murder rates. Widespread rent control policies–used across the world–often have serious adverse effects, like reducing total housing supply and quality, as well as driving up prices elsewhere.

The truth is that policy is complicated, and sometimes what seems like a great solution can make things worse. Avoiding bad policy decisions is important–and preventing them from happening can be a great path to impact in its own way. The important point is that policy is a tool for change, both good and bad, and that care is needed in the kinds of policy change you pursue if you enter a policy career.

What important problems can your government influence?

Another consideration to bear in mind is how important your country’s role is in tackling pressing issues. Most government ministries and departments require citizenship to work in them (though there are exceptions), so your direct influence tracks with the kinds of problems your government can influence. This shapes how promising it might be to pursue a policy career within your national government versus relevant NGOs, think tanks, or international organizations, which usually have looser nationality requirements.

Here’s an example: over 30% of the world’s ocean plastic waste comes from the Philippines, a country that contains only around 1.5% of the world’s population. By contrast, the US is responsible for less than 1% of ocean plastic waste. Because of this, we’d expect someone working in domestic waste policy in the Philippines to be able to solve far more of the problem than an equivalent individual in the US. For someone concerned about plastic waste in the US, it’d be better to find ways to affect policy where it matters more.

We think there are many other issues more pressing than plastic waste, but these problems are also distributed in a similarly uneven way. For instance, we think AI governance is a crucial issue, but as it stands, only a few countries, such as the US, China, UK, and the EU have significant influence in shaping relevant policy.

A nation’s wealth affects its policy priorities

A country’s wealth significantly shapes the severity and scale of its domestic issues, as well as its capacity to influence global issues. This creates different opportunity landscapes for policy careers depending on whether you’re working in a low-and middle-income country (LMIC) or high-income country (HIC).

Low-and middle-income countries tend to have more acute domestic issues. LMICs are countries with fewer resources and less economic output (as classified by their gross national income). These countries host the vast majority of people in extreme poverty and tend to have much higher disease burdens–often driven by preventable diseases like HIV and malaria.

For instance, malaria is all but eradicated in high-income countries, but kills over 600,000 people a year across the world–the vast majority in Africa. Similarly, air pollution kills over 8 million people per year, but death rates are highest among LMICs–often 20-30 times higher than in high-income countries.

This creates exceptional opportunities for domestic impact. A successful public health program in Bangladesh or Nigeria, for example, can prevent more deaths per dollar spent than similar programs in wealthy countries where baseline health outcomes are already much better.

As a crude rule of thumb, some of the biggest priorities within LMICs are likely to include health and development, economic growth, animal welfare, mental health, and climate change adaptation.

However, these issues vary widely across LMICs–this is a broad category that covers many countries with truly diverse challenges.

High-income countries often have more international influence. In high-income countries, the landscape is a little different. Many of the problems that afflict LMICs are often much less severe or very expensive to improve in high-income settings. This means there are usually fewer opportunities for domestic impact.

However, wealthy countries often have a disproportionate ability to influence international issues. They typically have larger foreign aid budgets, more advanced research capabilities, and greater influence over global markets. All of this means policy work in high-income settings is likely to be more promising when it focuses on ways to affect more global positive change.

Very roughly, the highest-priority problems within high-income countries might include international aid, animal welfare, AI safety, preventing global pandemics, climate change mitigation, and other global catastrophic risks.

Note that there are obvious exceptions to these classifications. Domestic issues in high-income settings can be highly severe and worth working on–but, on average, you’re likely to achieve better results elsewhere.

More generally, there are other important factors alongside wealth in determining a country’s international clout–like population size and cultural influence. For example, China is classified as an upper-middle-income country, but has an enormous influence on global issues. It’s one of the key players in the development of AI, and is likely to be a key player in any potential great power war. On top of this, it’s the world’s second-most populous country, meaning positive domestic policy changes, such as improving air quality, could lead to hugely impactful results.

How much can an individual contribute?

Despite policy’s overall capacity for enormous change, it’s less clear on the surface how much an individual might be able to contribute. Infamously, governments and international institutions are often large, lethargic institutions. Getting policy ideas up the governmental pecking order can be a laborious process.

Part of the problem is that senior civil servants and ministers are busy–there’s a huge amount on their plates, and usually many people competing for their time and attention. Because of this, policy is often a highly crowded area. Cutting through this noise isn’t easy. On top of this, political and professional incentives can get in the way of impactful policy areas. For instance, decision makers are often reluctant to pursue policies focused on important but rare risks like pandemics, prioritizing shorter-term benefits instead.

Despite these constraints, individuals can have surprising amounts of influence in policy work. We have a tendency to think of policies as just abstract proposals pushed forwards by institutions. But, in reality, there’s a real human side to policy. Policies that get implemented are often the result of an individual or small group pushing forward something they care about.

For example, national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic were often shaped by just a small number of experts and advisors, especially early on. These decisions had enormous implications for how the pandemic unfolded in each country. As a more specific example, in 2022, the UK became the first country in the world to recognize the sentience of crustaceans through law. This was heavily influenced by a report and written evidence from just a few researchers passionate about the topic.

Similarly, during research for our article on civil service careers in LMICs, we heard of the influence that so-called “policy champions” can have within government structures. These are people who persistently and enthusiastically pursue a policy within government. A competent, well-connected, and persistent person within government really can use their position to push forward policies that genuinely wouldn’t have occurred otherwise.

Resource spotlight

Some great examples of policy changes driven by individuals are available on the Mission Driven Bureaucrats website. It provides a host of case studies of individuals who have been able to almost single-handedly champion impactful policy reforms within government.

This dynamic doesn’t just apply to formal legislative changes; it also applies to more operational decisions made within government. When we researched our article on international aid, we heard it was common for civil servants to have influence over where millions of pounds are spent each year, even at a fairly junior level. This is true of other governments and departments, too. Choosing how to distribute these resources is a kind of policymaking, and it’s one that can do a lot of good if done well.

Bear in mind that there are usually still strong constraints on how funds or other resources are allocated. If you’re in control of your country’s budget for trains, you can’t just spend the money on improvements to animal welfare–at least if you want to keep your job. Even if you’re working in a more intuitively impactful area, like healthcare, there will be limitations that mean you probably won’t be able to rigorously prioritize.

Resource spotlight

This interview with Tom Kalil, who worked on policy with two US presidents, has some great tips for how to push through positive changes as an individual in a large organization.

Is policy a good fit for you?

As we’ve discussed, there are a lot of different career options in the policy space. This means that there’s a fair amount of variety between roles in terms of the personality types needed. Regardless, there are some commonalities that are important to consider:

You are resilient, patient, and able to navigate large bureaucracies. Whether you’re working within government or aiming to influence it from outside, making positive change is notoriously difficult. Governments and international organizations are large bureaucratic institutions, meaning it can take a long time and a good deal of persistence for your work to have positive results. This is true especially early on in your career, where you will have less autonomy to direct your policy focus and less influence over the overall process. Maintaining an entrepreneurial spirit and pushing for positive change within these constraints (without rubbing people the wrong way) is key.

You’re pragmatic about what’s achievable. Though big positive changes to policy do happen, incremental improvements are much more likely (and many attempts at change may fail). For example, during research for our article on aid policy, we repeatedly heard that various political, organizational, and cultural constraints made it difficult to implement large improvements to international aid.

However, small wins were often feasible given enough persistence and strategy. Small policy wins can often have a big positive impact–for instance, improving how billions of dollars are spent by even 1% can have large-scale effects. Combining ambition with a pragmatic, strategic mindset is a great help in these careers.

You’re socially adept and good at building professional relationships. A large share of policy roles involve extensive communication and networking with others. Being able to form and maintain productive relationships with lots of others is vital in these roles if you want to be able to get things done. This is particularly true if you’re working within a government, international organizations, or are in a political role. Note that this won’t necessarily apply as strongly to all roles, such as research roles in think tanks or academia.

Strategies and next steps

Testing your fit for policy roles

Here are a few ideas for quick ways to test your fit for policy careers.

Read existing policy research. Pick one of the think tanks on this list (whichever seems most interesting to you) and take a look at one of their recent research publications. Are there any things you think could be improved? Any important questions they haven’t answered? Could you see yourself doing this kind of research? This could be particularly useful if you’re interested in the research side of policy.

Follow a policy debate. One cheap test you can perform is to follow a parliamentary committee hearing from whichever country you live in, on a policy topic that interests you. Try to follow along and evaluate participants’ arguments, thinking about what you might say in response.

Take part in a policy advocacy event. If you’re more interested in the advocacy side of policy, consider finding policy advocacy/coalition events in policy areas you’re interested in that are often run by think tanks and NGOs. These can give some insight into policy work. They’ll also give you a great opportunity to practice the interpersonal skills that are often essential in policy work, as well as build a network that could come in useful later on.

Try our test task. Take a look at our test task, which we developed in collaboration with charity evaluator GiveWell. It involves creating either a report or a cost-effectiveness analysis of a global health intervention, and should take a few hours. Even if you’re mainly interested in other cause areas, this task will help you see if you enjoy critically analyzing often complicated and uncertain evidence–something particularly valuable in research policy roles.

Resource spotlight

Emerging Tech Policy Careers’ article on professional development covers some important considerations around the kind of skills and experiences you can develop to advance a career in policy. It’s primarily US-focused, but much of its advice is applicable elsewhere, too.

Considerations before entering the field

Prioritize policy areas. Policy is a powerful tool, but it needs to be directed towards the right problems to have a big impact. We expect that a large share of policy roles aren’t focused on the most pressing issues, so they have reduced scope for impact. Finding roles that can let you push for change on the most crucial issues, like some of those we mentioned earlier, is vital for someone who wants to have a great positive impact in policy.

You might need to get a graduate degree. An undergraduate degree is usually needed for any kind of policy work–but in many policy tracks (particularly research-heavy roles in think tanks and academia), postgraduate education will unlock important opportunities. Without a master’s or PhD, you may find you hit a ceiling in how far you can progress within some areas of policy. This could be a general policy graduate program, like an MPA or MPP, or you may need a more specialised educational background.

However, it’s worth noting the potential dangers of specialising too early in a specific policy area, which can close impactful doors later on. We highly recommend looking at policy job descriptions to get a sense of what education might be needed in areas you’re interested in, and at different levels of seniority. This isn’t a decision you necessarily need to make before you enter a policy career–it’s quite common to enter graduate school once you’ve already been working in policy for a few years.

Pursue promising fellowships and internships. In policy, taking up an internship or fellowship is a common path into and within the field. Because of this, there are a lot of opportunities available that are worth exploring, both within governments and policy orgs. We’ll cover some of these in the section below, and you can also take a look at our job board for other active opportunities. It’s worth noting that many of these opportunities are unpaid – and also that junior-level positions in policy are known for low salaries compared to the private sector.

Recommended resources for taking action

Fellowships and internships

Here are a few great recurring opportunities for those who are interested in policy, and are early-career or still studying:

- Emerging Tech Policy Careers have a huge list of opportunities for people interested in US tech policy.

- The World Bank hosts a large number of programs and internships that will give great experience of working in a large multilateral organization.

- The Talos Fellowship is an opportunity for people in the EU to gain experience in AI policy, with an 8-week program and optional 4-6 month placement.

- The Animal Welfare Institute runs an annual internship for law and policy surrounding farmed animal welfare.

- The UN’s Young Professionals Program is a prestigious opportunity for early-career professionals to gain experience in the UN.

- Find a full list of live internships and fellowships on our job board.

Online courses

These are courses that have been recommended to us by experts, or look like particularly good ways to upskill within policy:

- MIT’s MicroMasters in Data, Economics, and Design of Policy gives a great quantitatively-oriented approach to solving problems faced by LMICs. In fact, the large majority of its participants are located in LMICs.

- Bluedot’s Pandemics course gives an introduction to biosecurity, with lots of content relevant to policy.

- Your Role in Animal Advocacy, run by Animal Advocacy Careers, gives a strong introduction to animal welfare advocacy, with content relevant to policy change.

You can also explore

- Our articles on broad societal improvements and civil service careers in LMICs

- 80,000 Hours on careers that use policy and political skills

- The Institute for Progress’ Statecraft podcast

- Emerging Tech Policy Careers

- Mission Driven Bureaucrats by Dan Honig

- Impactful Government Careers